Q & A: Is it enough to remove a narcissistic leader from a church? Is there more to do?

Written by Dr. Chuck DeGroat, author of When Narcissism Comes to Church (IVP, 2020)

Over the years, I've found it challenging enough to get a narcissistic leader removed when credibly accused of abusive, narcissistic behavior. The podcast The Rise and Fall of Mars Hill shows a clear example of manipulation, bullying, misogyny, gaslighting, unethical behavior and pastoral malpractice within a system and by a pastor hailed as successful and faithful, lauded by many public Christians, and allowed to go on for years. Think of the many smaller churches where similar dynamics are happening.

I've been involved in a number of situations over the years where toxic leaders were removed, and it takes courage for an elder board or organization to do this. But these are often months-long processes and weary leaders sometimes feel like "we've done what we can, let's just move on." I'll sometimes challenge them to do the deeper work of dismantling and re-imagining the system around that leader to which I'll be met with an exhausted stare or look of confusion. I'll admit - I'm weary by then, too. It takes exceptional courage, resilience, and intentionality to dig even deeper.

Yes, there is more to do, much more.

In a course I teach, I often tell the fictional story of a seminary intern named Jill who faced a challenging situation in a toxic system. Jill is a young black woman at a church in the Chicago suburbs who finds herself sidelined quickly in her internship because "she just has a different style than us," as the senior pastor says.

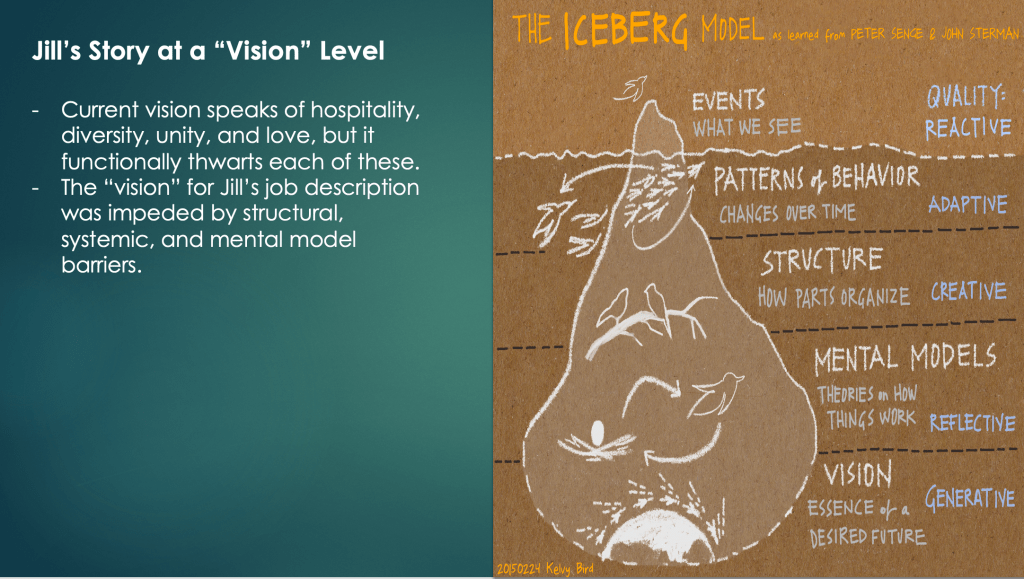

Below is an image from my course powerpoint drawn by Kelvy Bird and which illustrates the systems work of Senge and Sterman. In this "Iceberg Model," we often only deal with above-the-waterline realities, reducing deeper issues to matters of simple miscommunication or personality differences or variations on vision or mission. In Jill's case, she was at a church that spoke of a vision for diversity and inclusion, but when Jill brought her full self to conversations she was quickly shut down, told she was inexperienced, reminded that young leaders should listen much and speak little, and made to feel crazy for simply being curious and asking questions. As it turns out, Jill's experience mirrored that of previous interns, associate pastors, elders, even lay leaders who asked too many questions.

Beneath the waterline, we find at least one way (from Senge's work, primarily) of looking at deeper dynamics, beginning with persistent patterns (this is where the conversation begins to get real and a bit anxiety-producing within a system). Narcissistic leaders often blame problem people or one-off events or challenging interactions. They don't want to admit persistent patterns, especially their own. Further down we're invited to attend to structures and systemic dynamics, often implicit and unnamed. In Jill's case, the church could point to explicit structures that seemed to allow women to lead in certain ways, but we discovered implicit structures and invisible rules which protected men at the top. This implicates not just one leader but a whole system, structure, organization. Everyone is asked to do their part in identifying where and how they've propped up the real, operable structure. Even further below are mental models, and it takes even greater courage for a team or organization to explore their mental models. These include the often implicit assumptions, ideas, beliefs, pictures of the world, the liturgies we live by, which operate by default and inform everything we do. If a church begins to do this work, things can really begin to shift. It's challenging, humbling, painful, and it invites even deeper repentance. This is the dying that leads to the rising, a pattern I'd argue is more biblical than the current, toxic patterns. And that's what I remind churches - if you have any kind of theology of sin, then we can do this, because you'll simply be invited to name and deal with deeper and more pervasive levels of sin in your own life and organization for the sake of transformation, and this is the kind of Gospel work the church has been about for centuries! (That's not always very convincing).

I'll also use Maire Dugan's "Nested Theory of Conflict" to illustrate the multi-layered nature of the work. In Jill's case, she was counseled to change herself rather than speaking to the change needed within the organization. And to be sure, Jill was interested in her own "intrapersonal" growth (see my powerpoint slide below). Her own inner work was producing greater clarity and humility within her, and making courage possible in challenging ministry settings, in fact. At other times, still, she was told that her issue was merely "interpersonal," a disagreement between peers. To be sure, there was some disagreement and miscommunication. But while there was enough truth in each of these, they'd need to press in even further.

For the deeper work to be done, the church leadership needed to address why it chose the particular pastor it did, how it understood its own story, how it named particular values like hospitality or diversity but subverted them, even how its longer story of shifting from an urban to suburban location was caught up in larger white flight phenomenon. This would take courage.

In the end, Jill's curiosity was threatening because it poked at larger dynamics. And because this is fictional, we don't know the end of the story. Maybe from your own experience, you can fill in the end of the story. Or, in your situation, how far did the process go? Were the interventions mere above-the-waterline fixes or did they go deeper? What painful realities would need to be confronted if you were to go deeper in your organization or church?

Coming back full circle to the original question, what I've seen is that it's hard enough to confront the sin and toxicity of one leader. But when this happens, it's often treated as an above-the-waterline, 'now we've gotten rid of the problem' kind of thing. And as I've told churches, the real work only begins at the point.

Always...and you can take this to the bank... the patterns, implicit assumptions, problematic structures, mental models and assumptions, and more exist within the system, not in one person. Removing one person leaves a gap often filled in a predictable way with someone perhaps a little less rough around the edges, at first, but nonetheless a part of a toxic system. Amidst this, we ignore all kinds of unaddressed realities - past abuse, misogyny, unrepentant sin, patriarchal dynamics, patterns of dealing with money/conflict/anxiety, etc. - and we continue to perpetuate the old order (and, it seems to me that Jesus and St. Paul had a lot to say about dismantling that old order!)

Dismantling the old order is costly. It calls for a dying marked by real honesty, confession, repentance, and courageous systemic changes in personnel, patterns, structures, assumptions and more. This is why Jesus was crucified. The religious hierarchy of the day wanted a Zealot or a Pharisee to lead them, someone of an old order. This is why St. Paul was chased from town to town by Judaizers, men who condemned his radical new vision of redemption and a restored cosmos. But as my friends Laura Barringer and Scot McKnight remind us, there is the beautiful reality on the other side of the dying and dismantling, a community called Tov which is on the horizon if we'd have the courage and imagination to strive for it.

Grace and peace to you.